How do we determine whether a city is successful? These conversations often focus on population: successful places are gaining people, and unsuccessful places are losing people. This framing also has housing market implications. Growing cities need to create more housing for new residents, and declining cities need to figure out what to do with vacant or underutilized housing stock.

But population counts don’t show everything cities should know about their housing needs, and they may miss important trends. We should also pay attention to households, which include all people who live in a single housing unit. Even if a place is losing people, it could be gaining households, and that is more relevant to understanding housing demand and market pressures.

Comparing population and household change in three cities

When new US Census Bureau population estimates or American Community Survey results come out, researchers, policymakers, and the media dig into the numbers, often equating population gain with success and population loss with a problem.

This trend takes on regional dimensions. In recent decades, many Sun Belt cities—like Atlanta, Houston, and Phoenix—have seen growing populations, while populations have tended to remain stable or decrease in places in the Midwest or Northeast—like Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh.

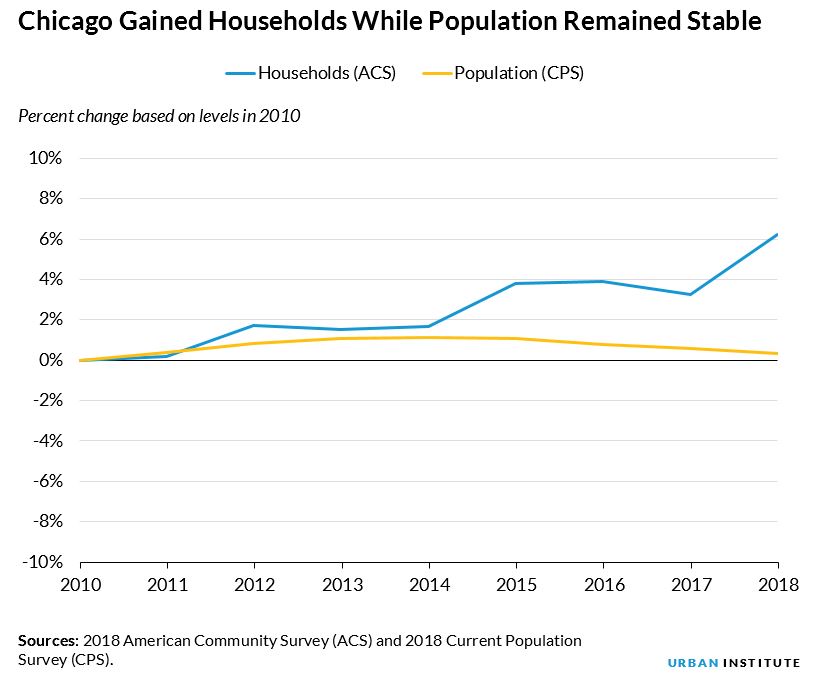

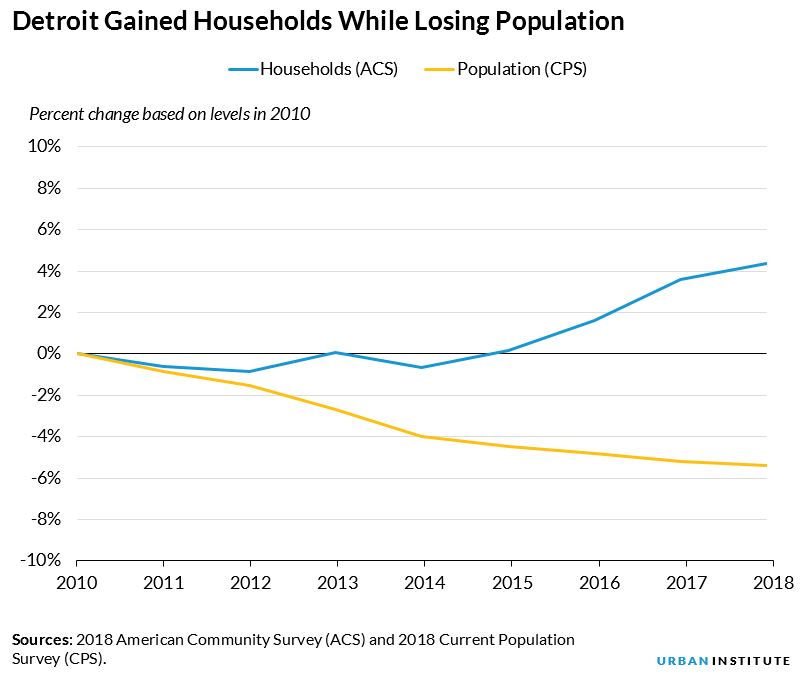

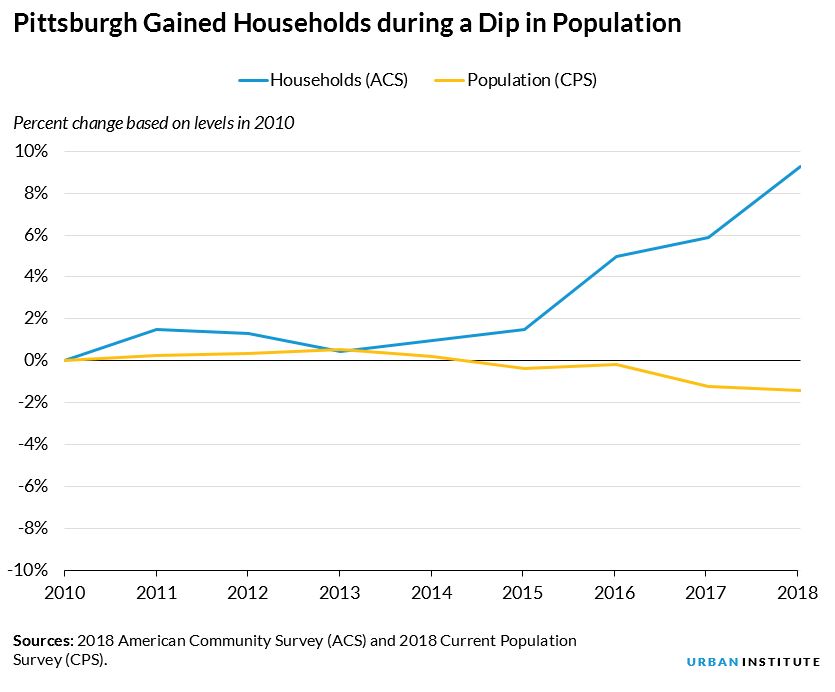

But despite their lack of population growth, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh have been gaining households in recent years. In Chicago, the population has remained stable, but the number of households has increased by 6.2 percent. In Detroit, while population dropped 5.5 percent between 2010 and 2018, the number of households has increased by 4.4 percent. And in Pittsburgh, even though the population dipped during the same period, the number of households increased by 9.3 percent.

So what’s going on?

These trends show that household composition is changing: fewer people but more households indicate growth in smaller households and, potentially, more demand for smaller units.

Other factors such as age, race, and income play a role in who is moving where and why. Chicago has sometimes been referred to as two-thirds Detroit and one-third San Francisco, with the city’s and region’s black population leaving in droves while the white population has been increasing.

In a segregated region, this trend has ramifications for neighborhood-level housing market pressures, including gentrification and displacement in some communities, as well as depopulation and disinvestment elsewhere. In this case, having extra housing stock in one neighborhood may not help reduce pressures in another.

Keeping data sources in mind

It’s important to pay attention to data sources when looking at these trends. The numbers reported here include household estimates from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) and population estimates from their Current Population Estimates program.

Because the ACS is a survey, the estimates always involve uncertainty. This uncertainty is generally reported as the margin of error, for which the ACS produces a range of estimates “expected to contain the true or population value of an estimate 90 percent of the time.” That margin of error is larger for households than it is for population, so it’s important to not overemphasize a single data point.

And because numbers jump around from year to year, it’s better to look at trends over time. ACS estimates show the number of households in Chicago dipping between 2016 and 2017 after edging up between 2015 and 2016. The estimates during that time were all within the margin of error, so claiming an increase in one year followed by a decrease in the next wouldn’t be supported by the data. But by looking at a longer time span, the relatively consistent upward trend since 2010 is more likely reflective of a real trend.

Household growth raises distinct questions about cities’ housing demand

This somewhat divergent trend between population and household counts has ramifications for local housing markets and how we think about them. The trend complicates how we think about “declining” cities or regions, especially in terms of housing demand. It also lends credence to concerns about housing affordability and displacement, even in places where population may be decreasing.

With more households, questions about where demand is increasing, what types of units are in demand, what units are being built, and how existing households are affected are important, even when a city is losing people.

Even though population will likely continue to be used as a shorthand indicator of a city’s trajectory, we need to be careful about what we miss when we rely on it too much for making decisions about housing market needs.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.