New York City’s new school chancellor Richard Carranza has vowed to enact policies that will alleviate school segregation. The promise does not lack motivation. New York City is considered one of the most diverse and progressive urban centers, yet its public schools are some of the country’s most racially and ethnically segregated in the country.

Much of the talk about integration focuses on the application process for selective high schools, but Carranza says he also wants to evaluate whether primary and middle school attendance boundaries encourage segregation. We ran the numbers and found that attendance boundaries tend to replicate local neighborhood integration, but enrollment patterns tell a different story.

Last year, I examined school attendance boundaries across the country and found that some districts manipulate attendance zones to influence school segregation. I established that while most districts do not use student assignment policy to address segregation, many gerrymander school boundaries in a manner that alleviates how much residential segregation is replicated in schools, while others do the opposite.

To assess whether New York’s school boundaries encourage segregation, I compared them with a hypothetical policy in which students are strictly assigned to the school closest their home. These counterfactual boundaries measure the residential segregation patterns of neighborhoods surrounding schools. We can then compare the segregation within these neighborhoods with segregation within actual boundaries to measure the policy’s intended level of school integration, assuming all students attended their assigned school.

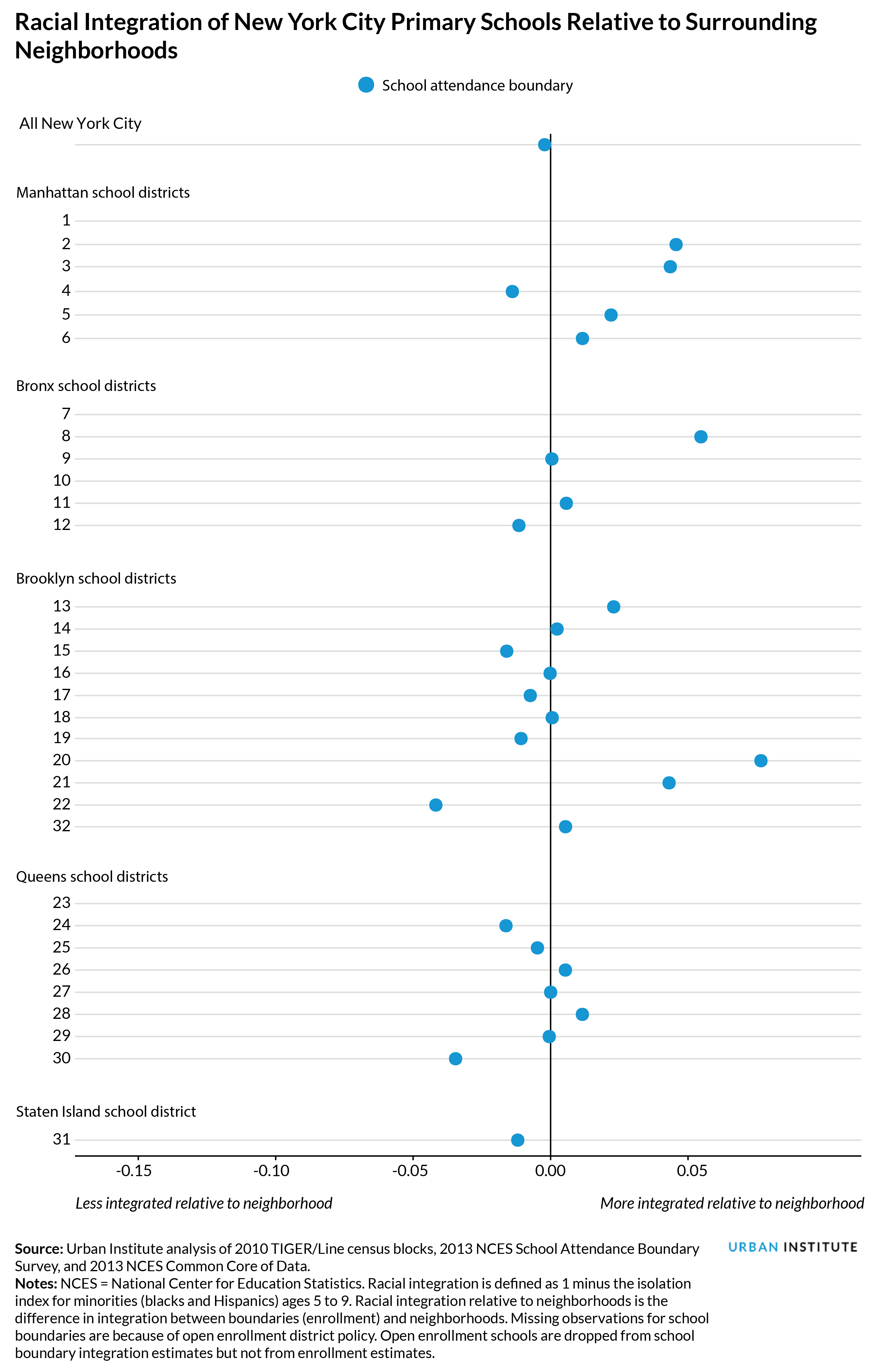

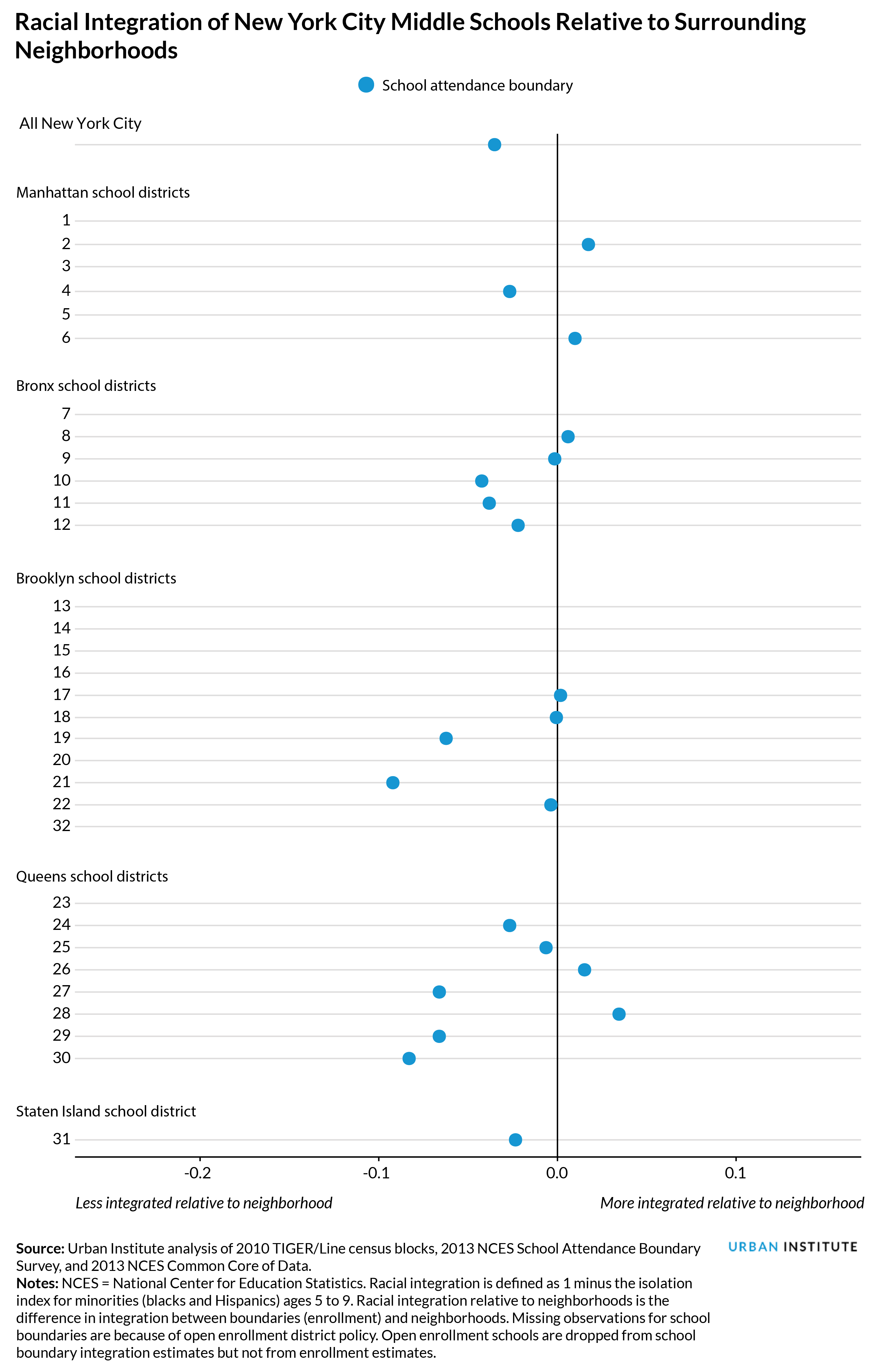

For the entire city in the 2013–14 school year, primary school boundaries decreased the average probability that an underrepresented minority student, defined here as a black or Hispanic student, shared school assignment with a nonminority (white, Asian, or other) student by less than 1 percentage point. In middle schools, boundaries decreased this probability by about 4 percentage points. This suggests that New York’s primary school boundaries essentially replicate residential segregation patterns, while middle school boundaries worsen school segregation relative to what one would expect from the demographics of surrounding neighborhoods.

These patterns vary across community school districts, however. In the Bronx, district 8’s primary school boundaries appear to be gerrymandered to increase racial integration. The average probability that minority students share school assignments with nonminorities is 6 percentage points higher than what would be expected from strict neighborhood schools. On the other hand, district 22 in Brooklyn decreases this probability by 4 percentage points, making it the district whose primary school boundaries encourage school segregation the most.

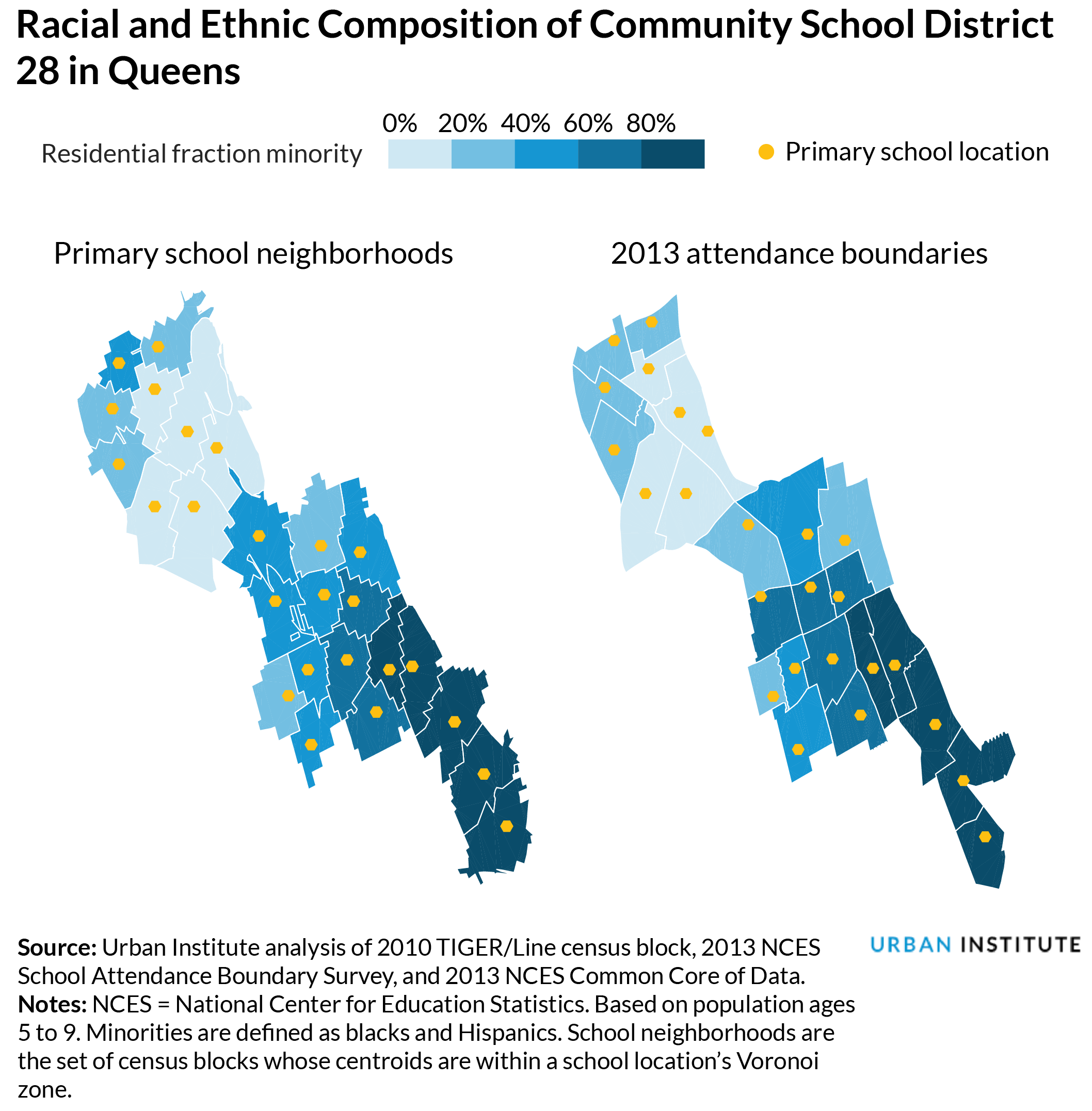

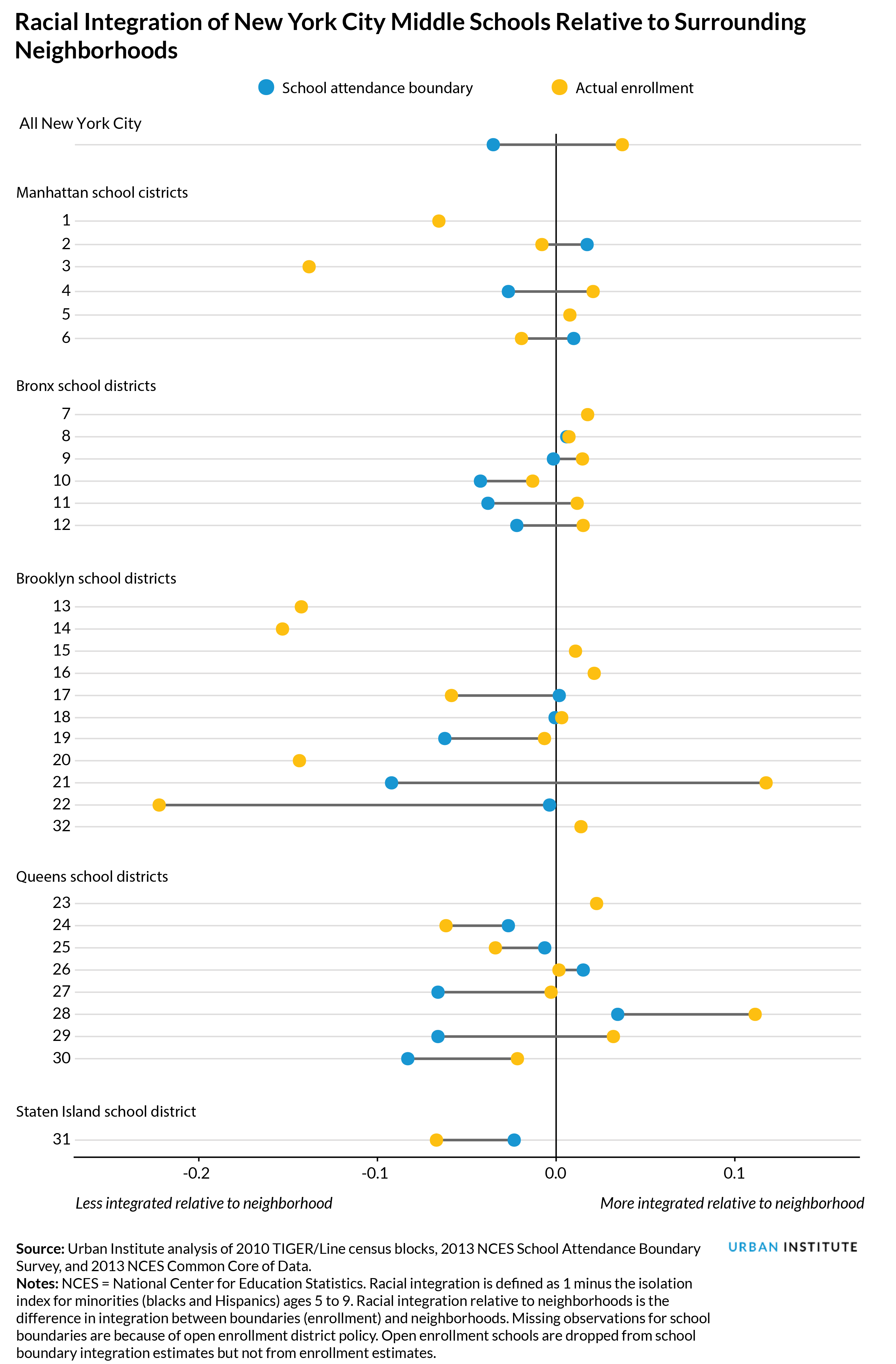

For middle schools, a significant fraction of community school districts drew boundaries that encourage segregation. Out of these, district 30 in Queens and district 21 in Brooklyn come in as the worst offenders, each lowering the probability that minorities and nonminorities share school assignments by approximately 10 percentage points. On the other hand, middle school boundaries in district 28 in Queens in 2013 were gerrymandered to promote integration, increasing the probability of racial interaction in student assignments by 3 percentage points.

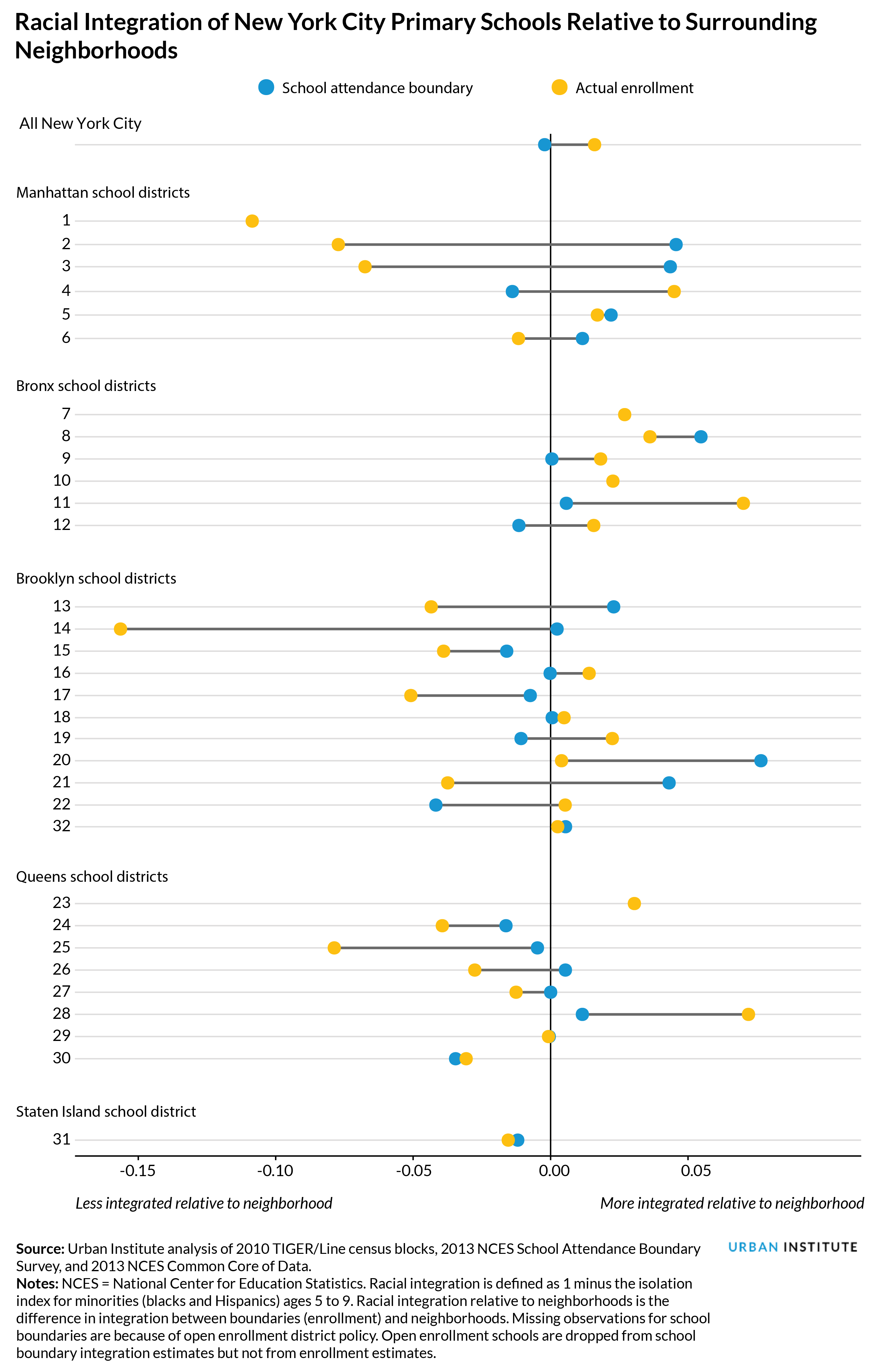

Though the assumption that families abide by default school assignments is useful to assess the intention of existing school boundaries, many New York families opt out by enrolling in choice public schools, charter, or private schools. To account for this, I measure school segregation as actually experienced by students using enrollment counts by race or ethnicity from the US Department of Education’s Common Core of Data. The differences are stark.

New York primary and middle schools are slightly more integrated than neighborhoods by about 2 and 4 percentage points, respectively. But this masks considerable variation across community districts.

Primary schools in Manhattan district 1 and Brooklyn district 14, for example, are less integrated than their neighborhoods—the probability that minorities attend schools with nonminorities is between 11 and 16 percentage points lower than what one would expect from the demographics of children living in the surrounding area. In middle schools, districts 22 and 14 in Brooklyn had the largest gap between enrollment and neighborhood integration.

Of course, there are exceptions. In the Bronx, district 11’s primary school enrollments are somewhat more integrated than residences. The district whose enrollments are the most racially balanced relative to surrounding demographics is district 28 in Queens, for both primary and middle schools. District 28’s integration gains are meaningful, increasing interaction across racial and ethnic groups by at least 7 percentage points.

New York’s education leaders could do more to draw school boundaries that steer families toward school diversity and racial balance. This is especially the case for middle schools in certain community districts. Such improvements would likely cost little in terms of additional daily student travel but might be controversial among the established community.

School attendance boundary gerrymandering alone is unlikely to fix school segregation, however. The evidence presented here strongly suggests that the bulk of New York’s school segregation stems from parents’ decisions—where to live, whether to take advantage of open enrollment or school choice policies, or which school they judge to be better—rather than from the districts’ school attendance boundary policy.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.